Westminster in Review

One hundred fifty years in the making, Westminster has always known what it stands for

by President Bethami Dobkin, PhD

When I was very young, I used to imagine living in an earlier century, perhaps the late 1800s, on a small ranch filled with animals near a western mountain town. I romanticized nearly every aspect: caring for livestock, growing crops, perhaps teaching at the town school, and making nearly everything I needed from what I had around me. That fantasy was borne from personal passions melded with the stylized imagery of Little House on the Prairie.

The reality of life in 1875 Utah was far different for both settlers and the Indigenous people whose lives they impacted. When Westminster University, known then as the Salt Lake Collegiate Institute, was founded with 27 students in the basement of the First Presbyterian Church of Salt Lake City, the region was largely inhabited by the Ute and Navajo peoples, along with other diverse groups: members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, who had founded the city a few decades earlier; emigrants working in mines and on the transcontinental railway; and US soldiers and travelers headed for the California Gold Rush. The early founders of the Collegiate Institute promoted an evangelical mission of conversion to nondenominational Christianity through education, and they committed to training future teachers to ensure educational excellence and interactive teaching in a nascent public school system.

During the first decade, the institute expanded rapidly to 245 students; it offered “graded classes similar to the best eastern public schools and emphasized personalized and progressive education. It acquired a regional reputation as an excellent residential academy,” writes R. Douglas Brackenridge in his 1983 book, Westminster College of Salt Lake City: From Presbyterian Mission School to Independent College.

Upon his retirement in 1885, Westminster’s first principal, John M. Coyner, issued an “Educational Creed setting forth the philosophical principles of inclusivism, equality, and integrity on which the Collegiate Institute would continue to operate. Included in the creed were statements affirming nondiscriminatory educational policies, equal employment opportunities and salaries for women, and rejection of union of church and state in educational matters,” according to Brackenridge. These values persist at Westminster University today.

The early founders of the Salt Lake Collegiate Institute both attempted to influence the religious, cultural, and political landscape of which they were a part and were also affected by the tumult of their time. The 1880s into the 19th century were marked by violence across the country—from the assassinations of President Garfield and President McKinley to lynchings and mob violence against African Americans in the South, massacres of Sioux Indians by the US Calvary, and riots and deaths of striking laborers to the Spanish-American and Philippine-American wars. Utah’s political environment was volatile as well, spurred in part by the anti-polygamy crusade of the 1880s. It made sense for the Institute to stress what Brackenridge refers to as “independent judgments based on observation and inquiry,” as well as citizenship and patriotism during this time. Technological innovations, such as the first telephones, box cameras, motion-picture cameras, and gas-powered flight, undoubtedly influenced the institute’s embrace of innovation and experimentation.

An expanding public school system and financial exigencies created by the Panic of 1893 challenged the continuance of the Collegiate Institute, but it persisted. The advocacy of trustee Rev. Robert G. McNiece led to the formation of Sheldon Jackson College in 1897, named after a Presbyterian minister, as a four-year baccalaureate institution associated with the Collegiate Institute. Bolstered by a renewed crusade against plural marriage, Jackson continued an earlier thread in Westminster’s founding of justifying support for the College as a response to Mormonism. Those arguments proved far less enduring for the success of the institution than its academic integrity, educational offerings, and contributions to the local economy. By 1902, and after having graduated one baccalaureate student, Sheldon Jackson College became Westminster College.

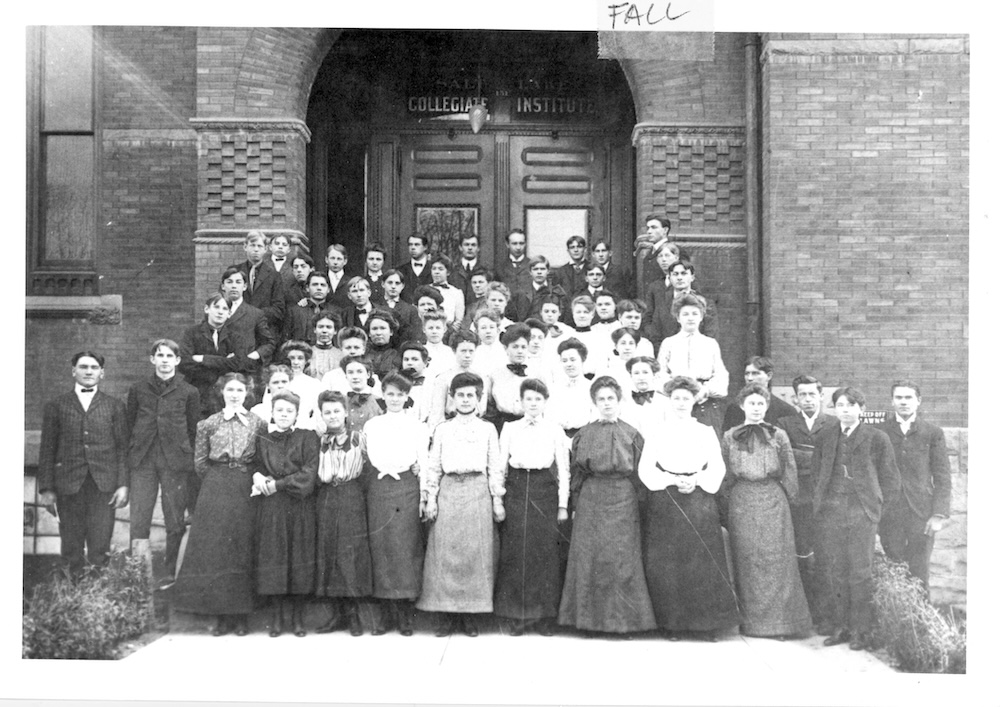

Salt Lake Collegiate Institute, 1880

The early founders of Westminster believed in the necessity of offering an answer to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints that, ideally, would convert their students to a Christianity aligned with their own. They believed that education itself, particularly if Bible studies and prayer were required as part of the curriculum, would lead students to convert to Presbyterianism, though conversion was extremely rare. While proclaiming the “evils of Mormonism”, the founders also understood the importance of separating believers from beliefs, or people from the theology that they represented. Members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints were then and continue to be represented in Westminster’s student body, and inclusion remains a core tenet of Westminster principles.

In the early 1900s, building a four-year residential college was slow and difficult, with only a handful of students, interruptions in class offerings, and limited local support. The transition to Westminster College, named after a doctrinal document embraced by the Presbyterian Church, required substantial philanthropy from supporters such as John Converse and Col. William M. and Jeannette H. Ferry, an increasingly ecumenical mission, substantial contributions and influence from the national Woman’s Board, the merging of the preparatory Collegiate Institute with Sheldon Jackson College, and movement of all operations to the present location on 1300 East. During the period up to and including World War I, and because of the impact of the war on student enrollment, Westminster focused on preparatory and junior college students while building a foundational liberal arts curriculum for all.

By 1935, Westminster had dropped the name and distinct identity as “Westminster Collegiate Institute” and become Westminster College, a four-year junior college. By 1949, after surviving the enrollment and financial pressures of World War II; diversifying the curriculum to include bachelors of arts and sciences degrees, as well as professional programs; instituting increasingly rigorous academic qualifications for faculty; and growing athletics and debate programs, Westminster College became a four-year baccalaureate institution.

In the decades that followed, Westminster continued evolving in ways consistent with its founding mission. In times when African American and Asian American students experienced restricted access to public facilities and discrimination off campus, Westminster upheld its commitments to equity. In the early 1960s, “when some universities instituted loyalty oaths and dismissed faculty whose political views ran counter to popular sentiment,” President Frank Duddy Jr. advocated academic freedom, according to Brackenridge. Leadership of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints explicitly endorsed the work of Westminster, and Westminster included a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints on its Board of Trustees. Westminster’s formal seal, “Pro Christo et Libertati” (for Christ and Liberty), was changed to “Advancing Independence and Diversity.”

Westminster, at its centennial, had weathered national depressions, wars, a global pandemic, and political and cultural upheaval, while expanding facilities, curriculum, and programs to meet the needs of students and serve the Intermountain West. The violence and cultural revolutions of the time were reflected in Westminster’s students and programs—from the establishment of a Black Student Union in the 1970s to Westminster’s declaration of independence from the Presbyterian Church. A new mission statement focused on Westminster’s commitment to liberal arts and professional programs. But despite the vibrancy and growth of students and facilities, Westminster faced a fiscal crisis. Throughout its history, Westminster had survived “by timely gifts, short-term loans and the use of undesignated endowment funds,” according to Brackenridge. In 1979, Westminster declared financial exigency. Over the next four years, academic departments and staff positions were eliminated, Ferry Hall was condemned, one-third of the board resigned, and Westminster was placed on warning by accreditors. On June 30, 1983, Westminster College closed for one day and reopened on July 1 as Westminster College of Salt Lake City.

Throughout the last 50 years, Westminster has continued in both responding to the circumstances of its time while looking to the future. The 1980s led to another period of reinvention for the college, fostering expansions of facilities, academic programs, and athletics. Gifts made by Berenice Jewett Bradshaw; Wilbert L. (Bill) and Vieve Gore, along with daughter, Ginger, and husband, John Giovale; and the George S. Eccles and Dolores Doré Eccles and Katherine W. Dumke and Ezekiel R. Dumke Jr. Foundation were pivotal in transforming and sustaining Westminster College. By the 1990s, Westminster was financially stable once again, with growth in the college’s endowment, the construction of new facilities, and significant increases in enrollment. The 1996 announcement of the 2002 Winter Olympics in Salt Lake City created additional opportunities to capture interest in and development of winter sports, leading to Westminster’s partnership with U.S. Ski & Snowboard and numerous Olympic medals for Westminster student-athletes over the years.

Consistent with the early years of its founding, Westminster’s more recent history reflects the changes of its times. When the population of college-going adults boomed after the 2008 financial crisis, so did growth in Westminster’s enrollment and academic programs. Growing success in athletics eventually led Westminster to join NCAA Division II in 2018. Interdisciplinary programs launched in the 1980s became a signature feature of Westminster’s undergraduate experience, both in the establishment of the Honors College in 2017 and throughout the curriculum in customized majors open to all students. The first graduate programs, begun in 1988, grew to as many as 15 programs spanning business, communication, education, and nursing, including doctoral programs in nursing practice and nurse anesthesia. These changes culminated in Westminster College becoming Westminster University on July 1, 2023.

Westminster’s sesquicentennial follows another period of history that has been called unprecedented and unimaginable. The declaration of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 was quickly followed by nationwide protests after the murder of George Floyd, impacts of climate change from rampant fires to hurricanes and flooding, mob violence at the US Capitol in an attempt to overturn a presidential election, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and the catastrophic escalation of terrorism and violence in the Middle East. In Utah, legislative changes during the decade have led to increased censorship in public schools, limits to women’s reproductive rights, restrictions on transgender access to health care and use of public facilities, and the prohibition of diversity, equity, and inclusion programs at all public universities.

Higher education has once again become a battleground for political and religious leaders who see education as a potential path to conversion. And, once again, Westminster stands proudly on the educational creed of inclusivity, equality, and integrity articulated by John Coyner. We are a unique and truly independent institution in the Intermountain West, committed to freedom of thought and discovery and to support of the search for identity and community throughout students’ educational journeys. We no longer look to the east for academic inspiration, nor to the west for frontiers to conquer. Our inspiration comes from the discoveries, creations, and performances of our faculty and students; our frontiers are explored for meaning, innovation, and shared humanity. Our core commitment to preparing students for lives of service now reflects and respects myriads of people and perspectives on campus and around the world, from on-campus classes to May Term Study Experiences and IPSL global engagement programs.

Our alumni continue to influence the region and the world as artists, scientists, nurses, educators, and entrepreneurs. They are actors and lawyers, athletes and scholars, award winners, medalists, and the first in their families to complete a college degree. They are leaders who can build on the strengths of the past, bring communities together, and imagine a future that sustains us all. This is Westminster University at 150 years: proudly independent, enduring in value, and bringing people together to respond compassionately and effectively to the challenges and opportunities of our times. It’s who we’ve always been—and who we will continue to be for another 150 years.

Salt Lake Collegiate Institute members, 1904

About the Westminster Review

The Westminster Review is Westminster University’s bi-annual alumni magazine that is distributed to alumni and community members. Each issue aims to keep alumni updated on campus current events and highlights the accomplishments of current students, professors, and Westminster alum.

GET THE REVIEW IN PRINT Share Your Story Idea READ MORE WESTMINSTER STORIES